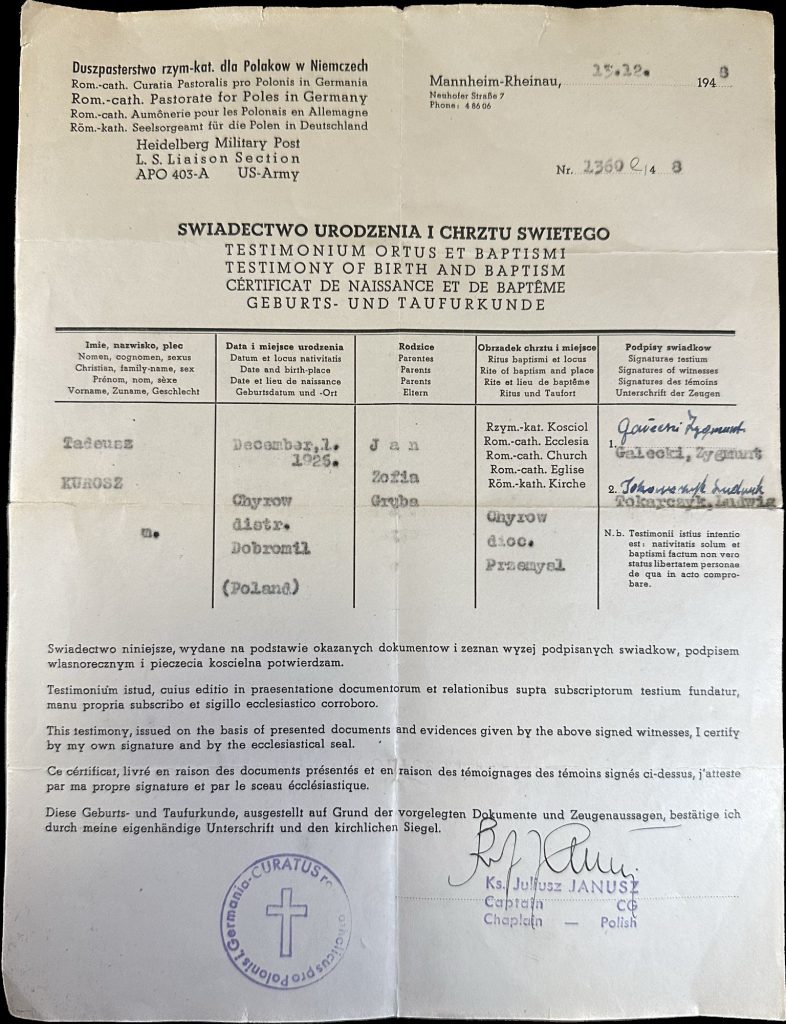

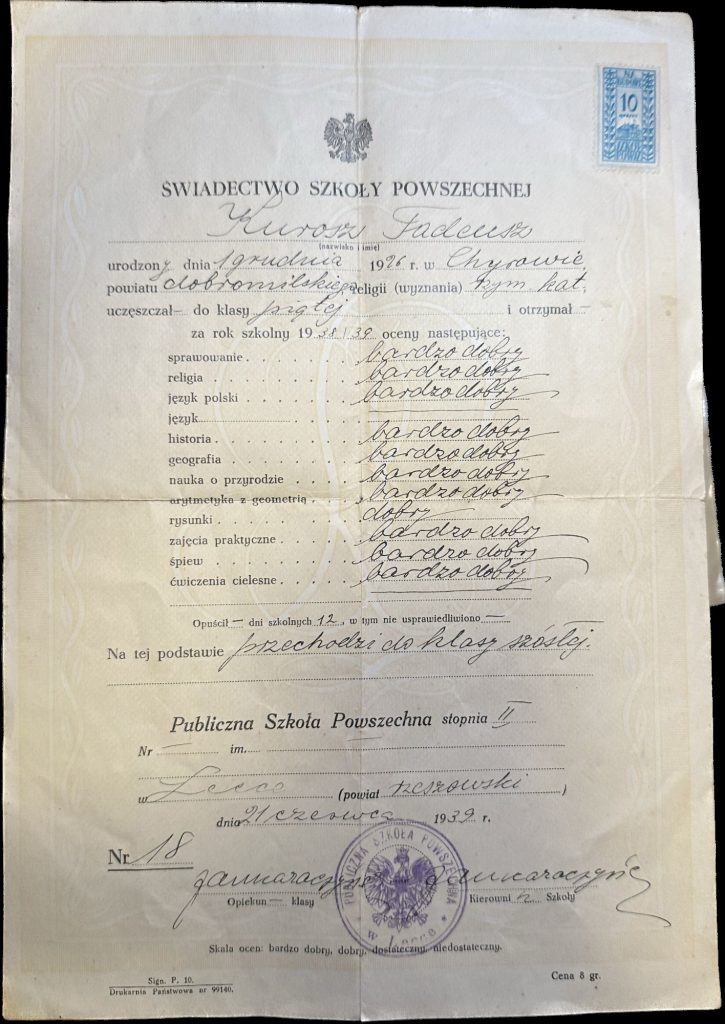

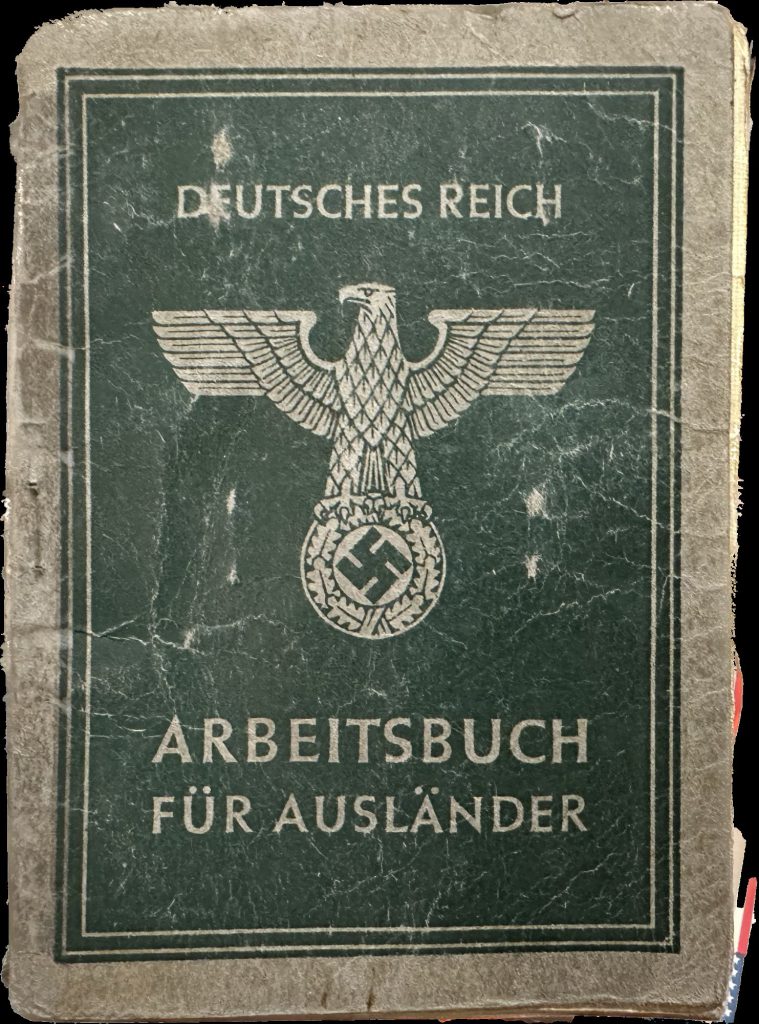

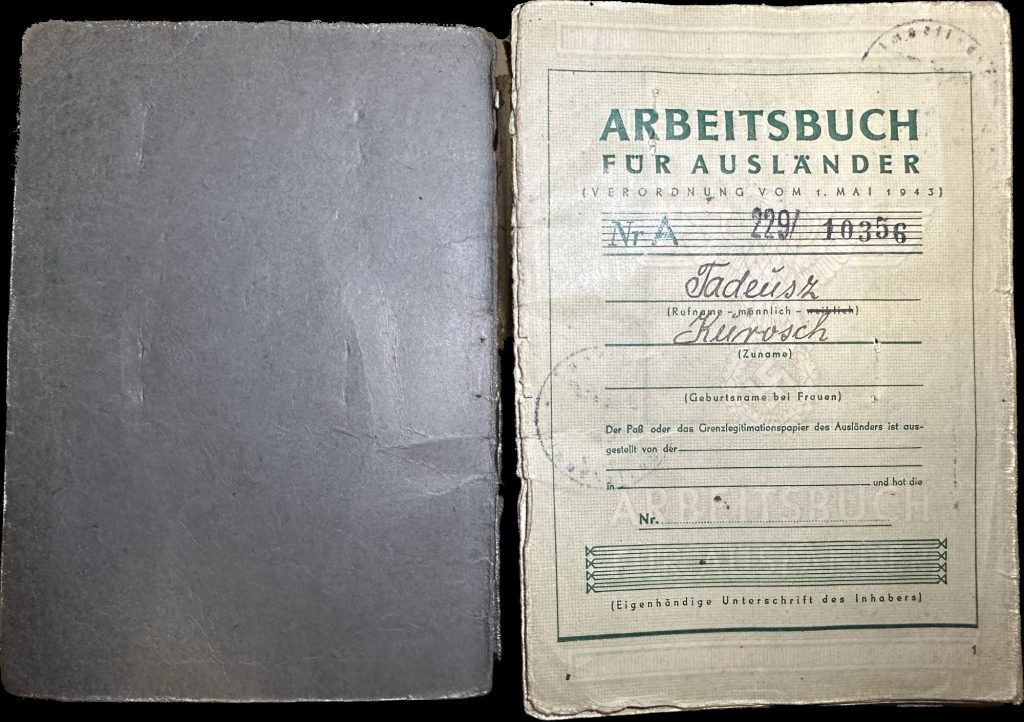

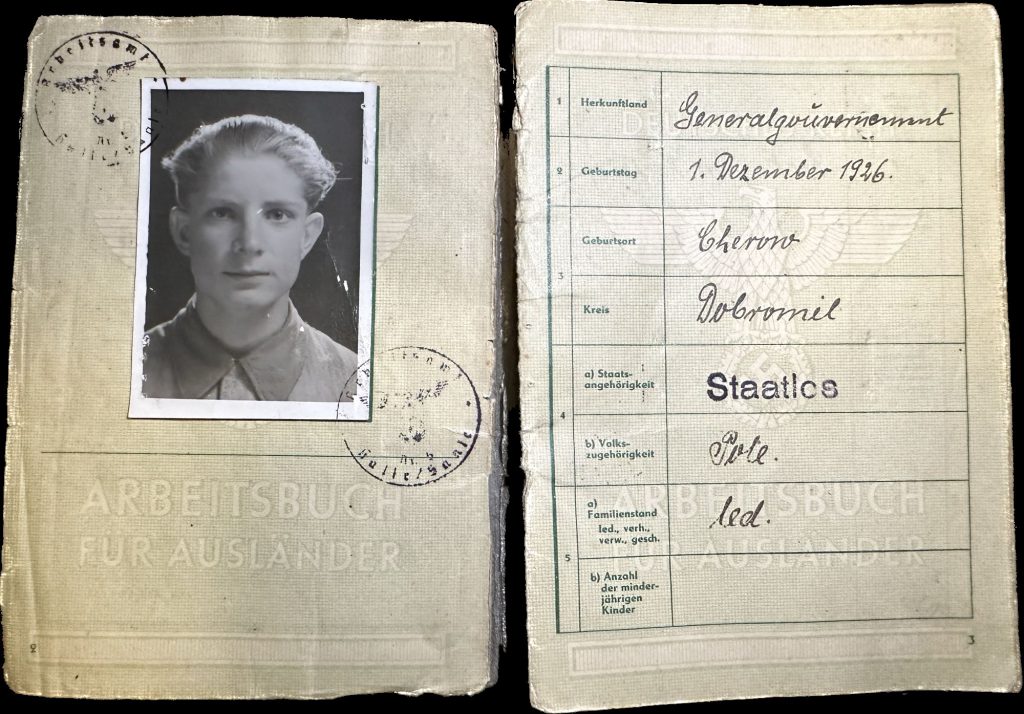

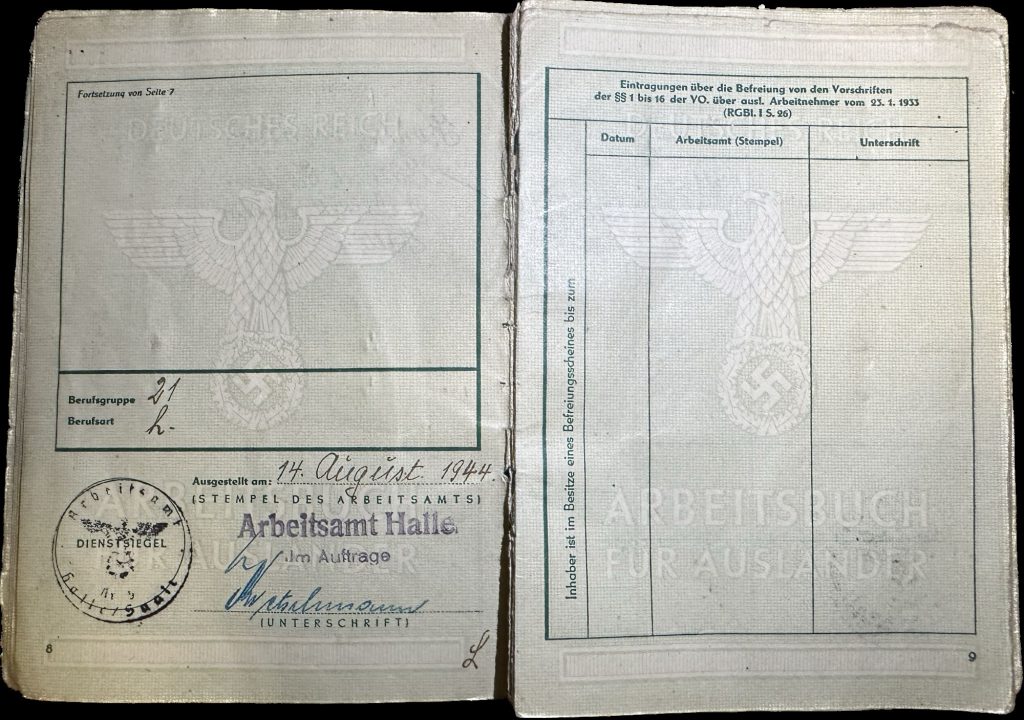

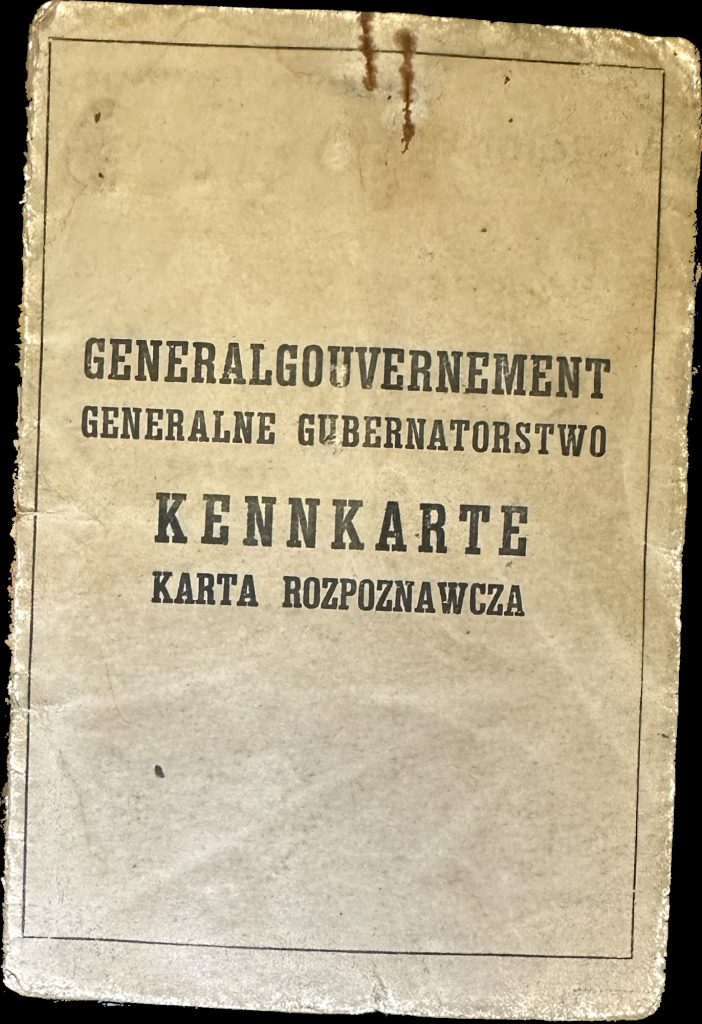

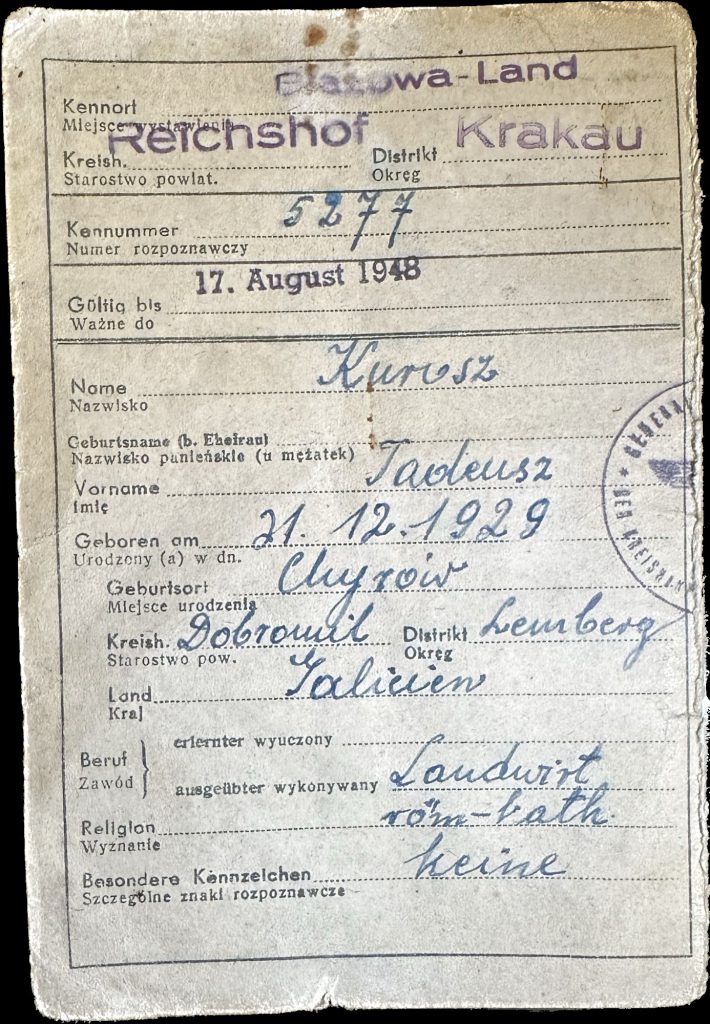

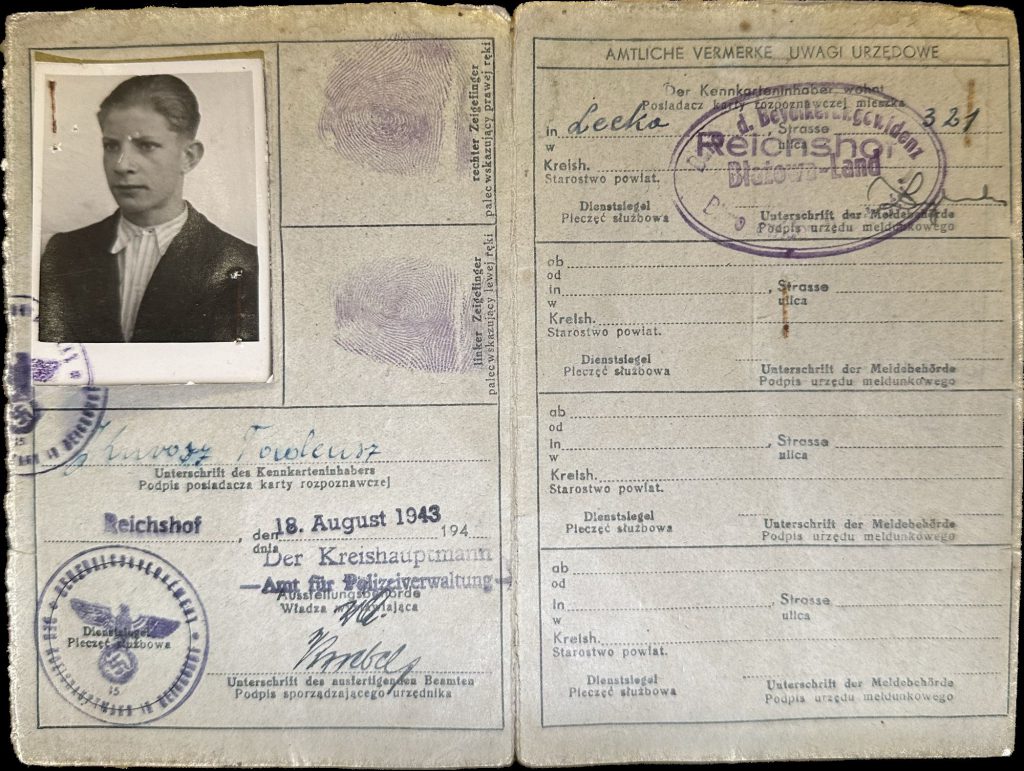

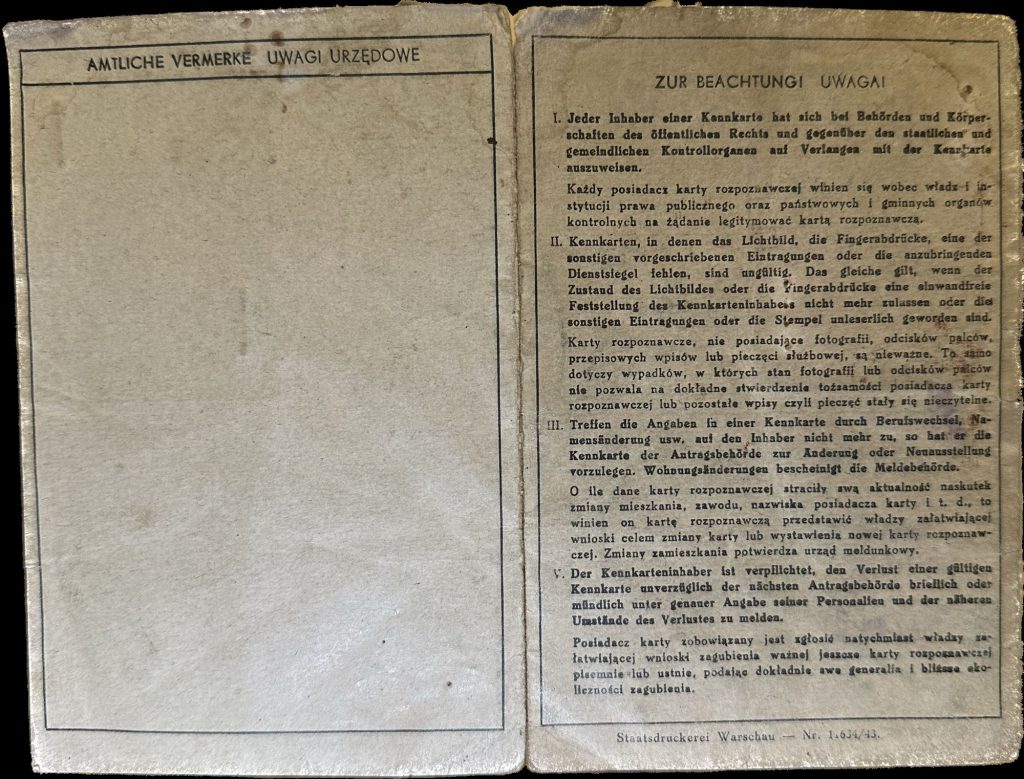

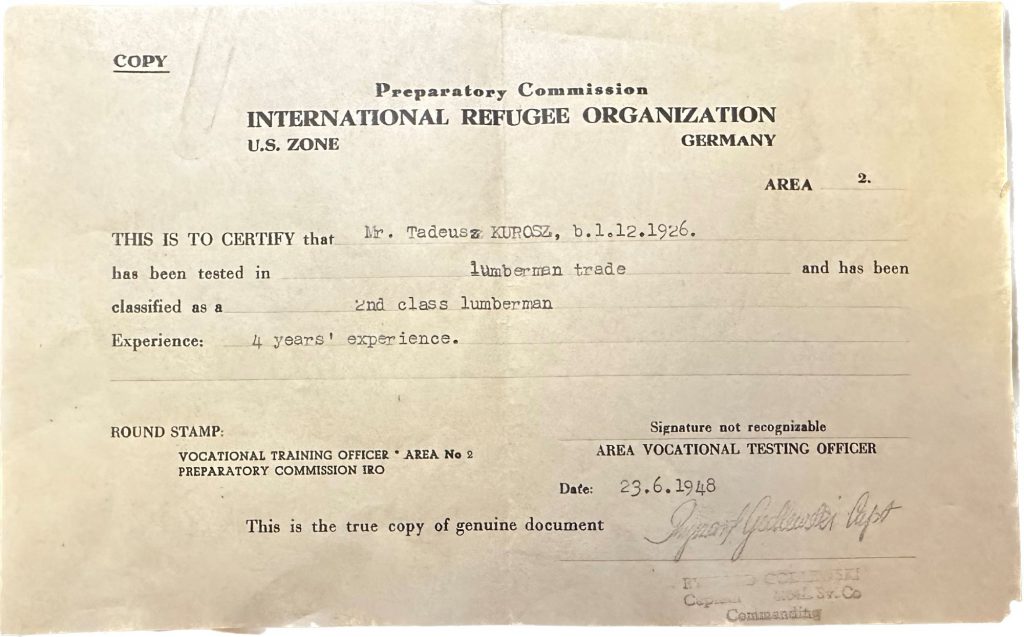

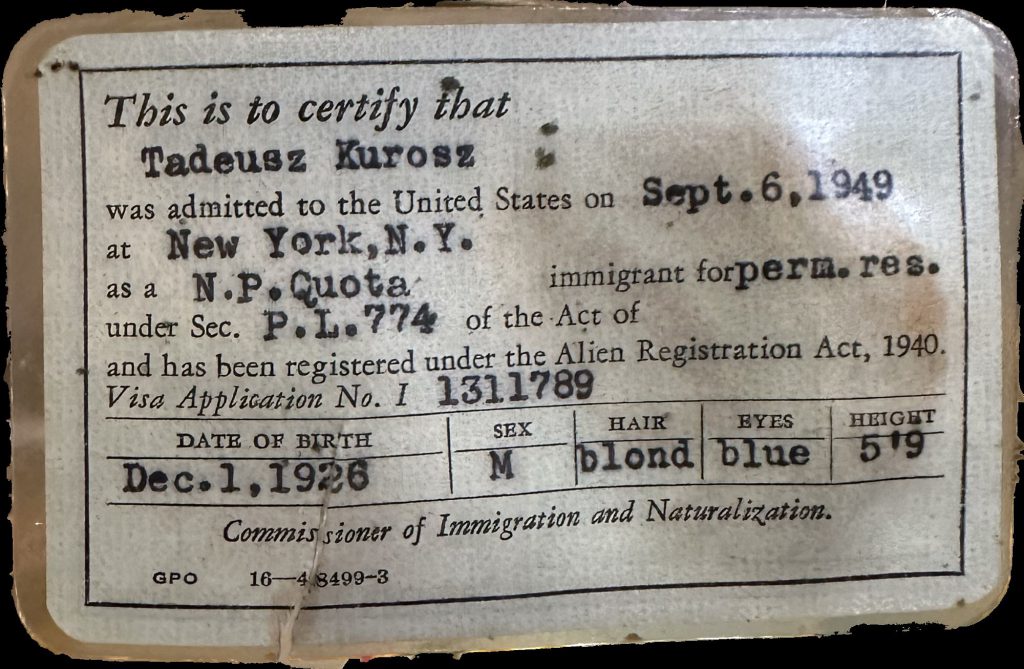

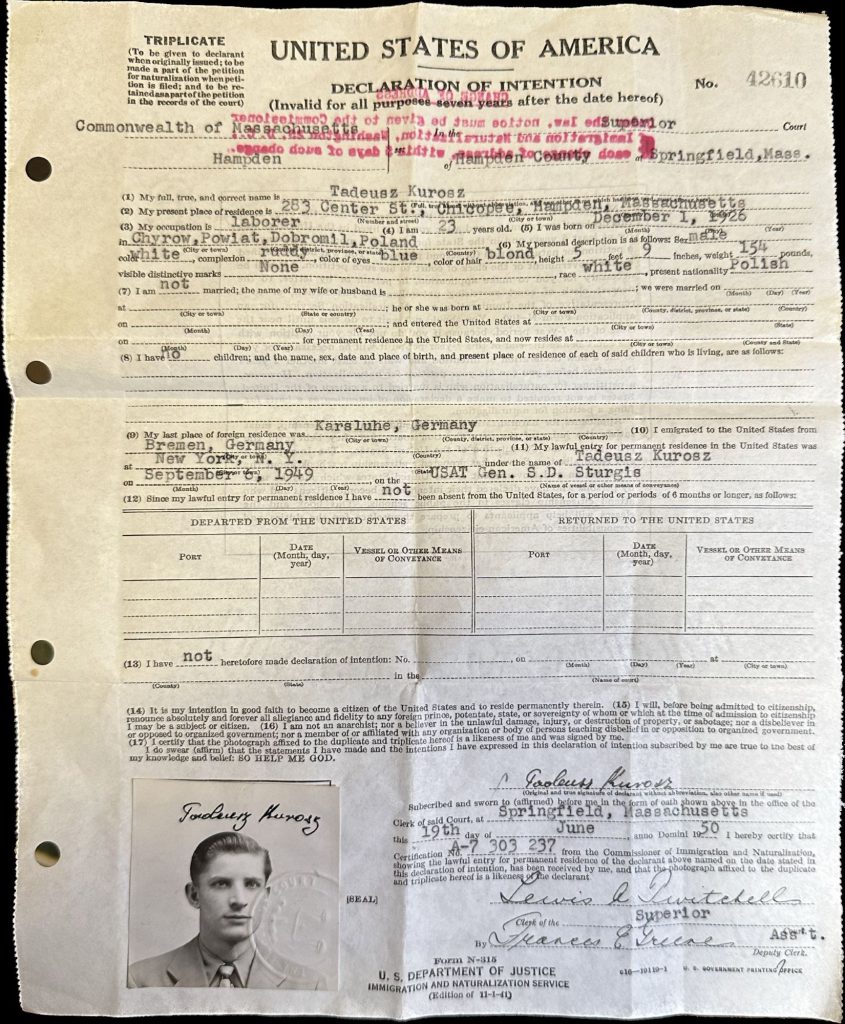

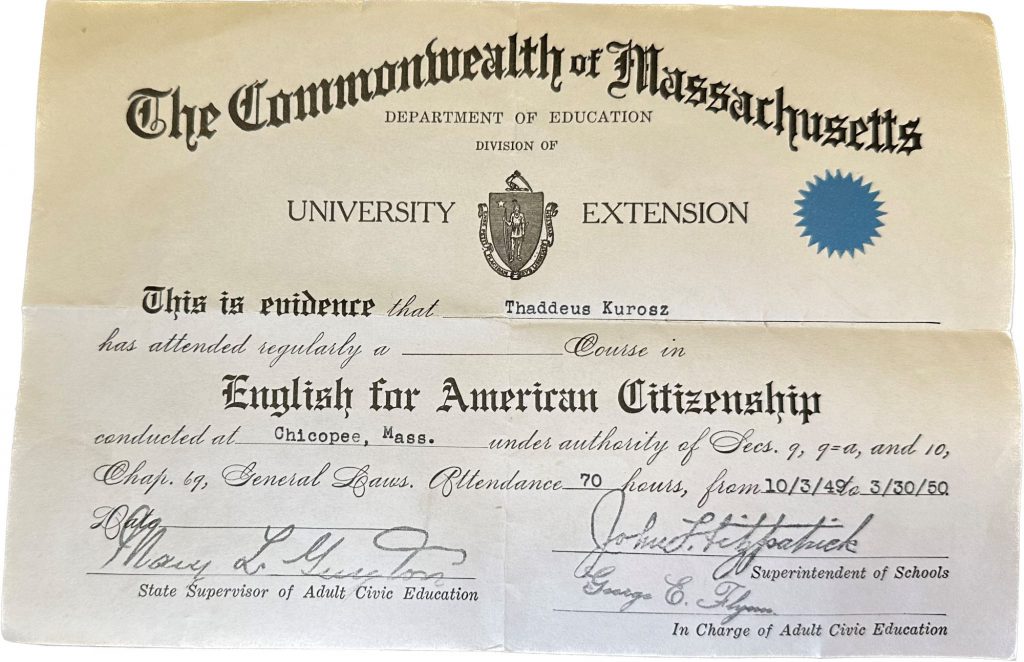

This Labor Supervision Identification belonged to Tadeusz (Thaddeus) Kurosz. Tadeusz was born on December 1, 1929 in Chyrow, in the Dobromil region of what was then Poland. He was taken as a teenager from his home by Nazi’s during World War II and was placed to work in several forced labor camps by the Germans. At the end of the war, he was liberated by U.S. forces and later was a guard for Allied troop supply depots. His workbook indicates that, by August 1943, he was stationed in Blazowa, a small town in the larger administrative district of Reichshof (Rzeszow). Both Blazowa and Rzeszow had Jewish communities that were destroyed during the war. Tadeusz was a Roman Catholic who was sent to labor camps in Germany. There, he was required to wear clothing with a “P” to indicate he was Polish. Working seven days per week, he often had to collect dead bodies after Allied bombing raids. After the war, Tadeusz served for four years in the U.S. Labor Service in Germany working at a supply depot and as a camp guard. In 1949, he came to Chicopee to live on Saratoga Avenue. He rented an apartment from his cousins, the Stonina family, who were also related to the former Chicopee City mayor, Anthony J. Stonina. He worked as a chemical mixer for the Monsanto Company for 37 years. He never married, nor did he return to Poland. He died in 2003 and is buried in St. Stanislaus Cemetery along with the ashes of his beloved dog Fritz. The documents in the collection include a German-issued passport, an American “Alien Registration” card, Tadeusz’s Declaration of Intentions to become a naturalized citizen, and much more.

Both his German identity card and his birth certificate state that he was born in 1929, but his Certificate of Discharge states that he was born in 1926. It appears that because the United States government normally expected adults to be at least 21 years of age in order to immigrate, Tadeusz lied about his year of birth to make himself older.

hometown—

The German Workbook was required for all workers, especially civilian forced laborers. In the years prior to the war, and during the war itself, the workbook above was the version that was the most common. But in May 1943, separate workbooks were created for foreigners. The workbooks were used when forced laborers were assigned a job and if that civilian forced laborer was assigned to a new job, their current boss sent their workbook to the new job, and allowed them to look through it, before the worker was to switch jobs.

Roughly 13 million people, from at least 21 countries across Europe, were coerced into forced labor in the German Reich. The groups of peoples in the forced labor camps fell into 4 categories: (1) Jews engaged in segregated compulsory labor, (2) prisoners from concentration camps, e-education camps, and prisons, (3) prisoners of war, and (4) the largest group, foreign civilian laborers.

The civilian forced laborers were treated differently depending on their nationality, with the two main groups being the Soviet and Polish. In the German Reich in August 1944, it was reported that there were 2.1 million Soviet and 1.6 million Polish civilian laborers employed. The Polish civilian laborers were only allowed to travel within specific boundaries, and both the Polish and Soviet civilian laborers, in particular, were detained in company-owned camps. Initially, Poles worked mainly in agriculture, but later, larger numbers of people were coerced into forced labor in the armaments industry. Some other positions they worked in were: as nannies in families, for the church in cemeteries, or in municipal services, such as garbage collection. But these special work cases were only to replace the missing workforce.

(Arolsen Archives)

Błażowa, Poland was a shtetl, a small Jewish town or village in Eastern Europe. On June 26, 1941, the population of 930 Jewish people residing in Błażowa were forcibly moved to the Rzeszów Ghetto. Which became a shared fate amongst many other neighboring shtetls.

In September of 1939, Rzeszów was occupied by German forces. At the time, there was roughly 14,000 Jews living within the city. Many of the inhabitants were put into forced labor; mainly manual work including: office work, street cleaning, and bridge repairs. While working, the Jews were beaten, and some Orthodox Jews were injured by having their beards and side locks physically torn off of their faces. Synagogues were vandalized and looted, and wealthy Jewish apartments were taken over by the German soldiers. Even the Jewish hospital was not able to escape when it was turned into a military installation.

From December 1, 1939 and on, Jewish citizens in Rzeszów were required, from the age of 12 and up, to wear a white armband with the blue Star of David attached to it. All around the city, their movements were restricted, and traveling by train was forbidden. They also had a 7:00p.m. curfew.

On December 17, 1941, it was announced that Rzeszów was a ghetto. In the year prior, the Germans had renamed the area Reichshof. By the end of the month, all of the Jews had moved into the ghetto. On January 10, 1942, the Rzeszów ghetto was sealed with walls and wooden fences with barbed wire. By this time, the total population of Jews imprisoned in the Rzeszów Ghetto was up to 12,500. Only those who were being taken for forced labor were permitted to leave the ghetto.

Behind the walls, diseases and starvation spread rapidly. Epidemics of dysentery and typhus killed many, which resulted in large numbers of bodies being piled in the streets. The Judenrat, the 30-man Jewish Council, was granted permission to grow potatoes outside of the walls, which aided in the starvation of thousands, but could only help so much. They also set up a small hospital, which did not have beds or medicines, but was an attempt in aid.

In spring of 1942, a number of forced laborers were transferred to a labor camp in Biesiada. In addition to the Jews from Kalisz and Łódź, other Jews from the vicinity were brought to the Rzeszów ghetto. Soon, the overcrowding became severe, which resulted often in more than one family having to live in a room.

On June 25-27, 1942, the overcrowding in the ghetto became intense with the transfer of Jews from Łańcut, Tyczyn, Kolbuszowa, Głogów, Małopolski, Sędziszów Małopolski, Czudec, Jawornik Polski, Błażowa, Niebylec, and Strzyków to the Reichof ghetto. Once they were all settled into the Reichof ghetto, three families were living in a single room. By early July 1942, the ghetto population had increased to approximately 22,000 people. Around the same time, German officers mandated the evacuation of certain peoples from the ghetto. The Jews were told to bring only a few essential items and enough rations for roughly two days. Nearly 20,000 Jews were deported and hundreds were shot.

In August 1942, women with children were ordered to register for ‘light labor.’ This seemed like a positive sign for those living in the ghetto. Women who had no children, ‘borrowed’ a child from their neighbors so that they would also only be ordered to ‘light labor.’ However, as they reported for the registration, they were surrounded by SS troops and then sent to the Belzec Death Camp, where they perished. Also sent to the Belzec Death Camp were approximately 1,500 Jewish children who were loaded onto trucks and were sent to their deaths.

In September 1943, the ghetto came to an end. The remaining inhabitants, approximately 3,000 people, were assembled, and some were selected for the forced labor camp in Szebnie and many of the others were deported to Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

By the end of the war, only about 450 Jews remained in Reichshof (Rzeszów).

(Holocaust Historical Society)

In 1945, over one million Polish immigrants, volunteers, and exiled political leaders eagerly became a part of the U.S. Army’s Labor Service. In no time, they would become known as the “Polish Legion,” who wished for the opportunity to fight for Poland’s freedom.

During the war, the U.S. armed forces needed people-power by the thousands to aid in protecting the military installations, warehouses, prisoner camps, prisons, army offices, and civil representatives of the Western powers. At the same time, the British Army also set up Polish guard units.

The Labor Service (LS) included several types of units:

1. Companies and platoons performing the functions of external protection of military facilities (Guard Companies);

2. Patrol squadrons manned airports, warehouses, and other installations of the U.S. Air Force (Guard Squads);

3. Transport Units (Truck Companies);

4. Fog Companies. In the 1950s, two units were responsible for making artificial fog. These were the only such outfits that the U.S. Army had in Europe at the time;

5. Labor Units, designated to construction projects associated with fortification and development of U.S. Army bases (this mostly entailed hard labor and the laborers were mainly non-Poles).

(The Polish Review, Vol. 57, No. 4, 2012)

With the opportunity to become a part of a group to fight back the oppressors, former prisoners of war or concentration camps, who had been dehumanized, were now allied soldiers against Germany. At the same time, it was the next best choice than returning back to Communist-occupied Poland. Several of the Polish military officials in the U.S. Army had also been a part of the Polish Army pre-war.

In May 1945, the first Polish guard units were established by the U.S. Army. There were detailed rules regarding the Polish guards being tasked to take the place of American soldiers. They were required to pass basic training and were almost immediately considered a full-fledged U.S. soldier.

Some of those who volunteered for the LS, were in groups. One example is from mid-1945. The Polish group known as Holy Cross Brigade (Brygada Świętokrzyska) joined the LS, and fought and covered territory from Poland to Czech territory. In August 1945, they were enrolled in Guard companies. The group that was called the “Salamanders” consisted of 200 Polish officers and 6,250 privates, which formed 25 companies. But there were political differences in the Labor Service that reflected a lack of uniformity among the guardsmen. For example, the “Salamanders” held their traditional anti-German attitude as part of their political ideology for much of the war.

In the beginning, the Labor Service held honor and respect for the Polish ranks. But overtime, the U.S. Army imposed a limitation on the privilege of using Polish badges. In 1946, the special training school, Training Centre of Tadeusz Kościuszko at Mannheim, was developed along with several others. Overall, over 40,000 Polish guards were trained, and up until 1947, the Poles made up roughly 80 percent of the U.S. armed forces auxiliary units in Europe.

(The Polish Review, Vol. 57, No. 4, 2012)

Author: Buffy Gudrian, History major, Elms College.

Stephanie Afonso, History major, Elms College.